The official opening ceremony of the International Year of Camelids (IYC) has been scheduled for the 4th December at FAO headquarters in Rome. It will happen in the form of a 90 minute side-event during the FAO Council. While Civil Society and pastoralists/small producers have each been allotted five minute slots in the draft programme of the event, their physical presence is very much in doubt, due to lack of resources for their travel as well as the difficulty of obtaining a Schengen visa at such short notice. At the informal IYC support group, we are hoping that it will be possible for them to be present and represented at least virtually. Because their visibility is crucial, these two constituencies should not leave the field to wealthier stakeholders who can afford their participation.

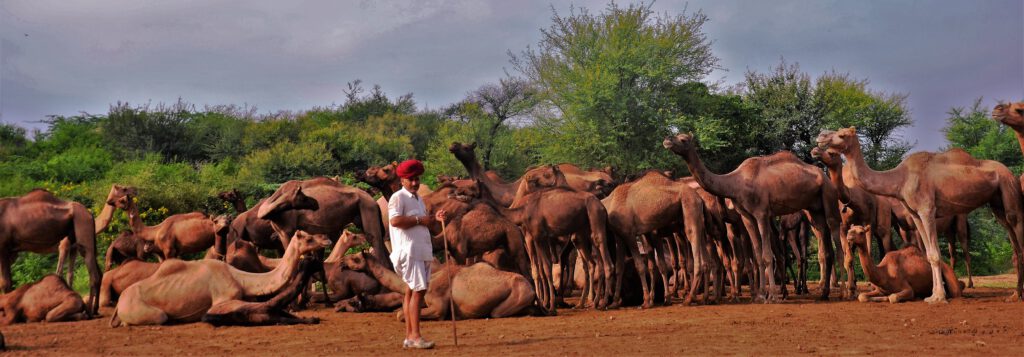

The official slogan for the IYC is Heroes of Deserts and Highlands: Nourishing People and Culture. This has a nice ring, but the ‘traditional’ communities and indigenous peoples who in turn are nourishing camelids – whether it is alpacas and llamas in the Andes of South America, dromedaries in the arid zones of Africa, the Middle East and South Asia, or Bactrians in the steppes of Mongolia and China – are also true heroes. If we, as humanity as a whole, want to benefit from the special adaptations and potential of camelids in generating food in extremely marginal areas, then industrial scale stall-feeding systems as they have cropped up in oil rich countries are not the answer. These may look shiny and scientific and progressive compared with the mobile husbandry systems in which camelids have been raised until now, but they are basically unsustainable, depending on imported feed and fossil fuels, apart from not providing an environment in which camels thrive and are happy. Like people, camels love to wander around and browse (‘shop’) on different types of plants, composing menus according to their own individual tastes. As one of the members of our network, camelologist Dr. Raziq Kakar, puts it ‘camels are like South Asians – they need spicy food and not a bland institutional diet’.

In short, putting camelids into stall-feeding systems with standard diets of alfalfa hay and grain defeats their ecological purpose. They are biologically designed to be kept in nomadic systems, and to do so requires the knowledge and dedication of traditional or modern pastoralists who are willing to undertake the hardship of managing and careing for camelids in marginal areas with harsh climates. And that is a challenge ever fewer young people want to engage with – and who can blame them, considering the hardships of living in remote areas. The average age of alpaca breeders in Peru is mid-sixties; in India it is probably similar for dromedary breeders.

All of us in the camelid world are grateful that the International Year of Camelids will shine the spotlight on our favourite animals. But we must make sure that the IYC’s activities and outcome support their guardians: the communities who have nurtured and nourished them over thousands of years and for whom these animals are co-creatures and not meat and milk generating units crammed into feedlots or mere status symbols. A Civil Society statement that already has been signed onto by 23 organizations calls for carving out an alternative cruelty-free development trajectory that conforms to the worldview of traditional camelid keeping communities and avoids industrialization.

The organizations elaborate the kind of support and interventions they wish for:

- Enabling mobility and ensuring secure access to ancestral grazing and browsing areas for our camelid herds to thrive, for example by recognizing them as Indigenous Community Conserved Areas or Territories of Life

- Investing in decentralized infrastructure, such as networks of mini-diaries and local processing facilities to link camelid herders in remote areas to value chains, while also respecting and supporting our traditional ways of processing,

- Fostering camelid-herding community organizations and their agency,

- Respecting and building on our traditional knowledge and related local innovations,

- Strengthening provision of camelid healthcare, including research into emerging diseases,

- Supporting investment on people-centred and -controlled camelid research and development,

- Recognizing camels as co-creatures and establishing camelid welfare standards into policy and practice worldwide,

This statement made by people and organizations deeply involved with camelids on the ground should be taken serious. Their voices must be heard! For this reason FAO must make an effort to give them visibility, listen to their requests, and make adequate resources available for their representation in events relating to the IYC. As another network member, Cecilia Turin puts it :’It is the same as with gender blindness. If you know there are gender gaps and you dont do anything to ensure equal participation, then you are reinforcing the status quo and so increasing the gaps.’ We must make sure that not only those who can afford it are represented at IYC functions!